Introduction (Abstract)

Introduction (Abstract)

Article by: Gianni Frisardi

|

Abstract

Rethinking mastication: from “occlusion” to a neurofunctional paradigm

Mastication is not a mechanical consequence of teeth and joints. It is a neuro-regulated behavior shaped by periodontal and muscular proprioception, trigeminal reflex circuits, cortical modulation, and adaptive plasticity. Clinical reality repeatedly exposes a paradox that classical biomechanics struggles to classify: functional symmetry can persist even in the presence of evident morphological asymmetry. This is not a marginal curiosity but a diagnostic warning sign: the stability of the masticatory system cannot be inferred from shape alone.

In Kuhnian terms, contemporary dentistry—particularly in the domain of occlusion—often behaves as “normal science”: it refines rules and techniques inside an accepted framework, while accumulating anomalies that are not easily explainable by the dominant model. The presence of these anomalies does not weaken the scientific structure; rather, it signals maturity: a system that recognizes its own limits and becomes capable of paradigm evolution. Masticationpedia starts from this epistemic point: not to discard classical dentistry, but to extend it, shifting from a static biomechanical interpretation toward a functional, neurophysiological, and systems-based view.

This shift is also methodological. Modern clinical research has long relied on statistical inference as a gatekeeper of truth, with the p-value functioning as a binary passport for acceptance or rejection. Yet, a “silent revolution” is underway: the rigid use of statistical significance has been challenged, and scientific reasoning is progressively moving toward contextual inference, model-based approaches, and epistemic transparency. For complex biological systems—where variability, adaptation, and interaction dominate—this transition is not optional. It is necessary. The masticatory system is a paradigmatic example: it is measurable, but not reducible to a single metric; it is structured, but not linear; it is adaptive, but not infinitely compensatory.

A further implication is interdisciplinarity. When the masticatory system is treated as a complex clinical object, the traditional “physical paradigm” (deterministic simplification and isolated variables) becomes insufficient on its own. An “engineering paradigm” becomes indispensable: knowledge is treated as an epistemic tool—something that must work across disciplines to solve real clinical problems. This requires common languages between dentistry, neurophysiology, pain medicine, biomechanics, systems science, and clinical epistemology. Masticationpedia is explicitly designed as such a translational environment: a platform where clinical observations are not merely described, but reorganized into a coherent diagnostic framework.

The clinical core of the chapter is the re-interpretation of “malocclusion”. The term itself carries a value judgment (“bad closure”) that is not always supported by functional evidence. The literature is vast, yet truly interdisciplinary differential diagnosis remains scarce. This mismatch suggests an overuse of morphological labels without sufficient investigation of neuroadaptive function. For this reason, Masticationpedia introduces a more neutral and clinically honest concept: Occlusal Dysmorphism. The rationale is simple and consequential: not all asymmetrical occlusions are pathological; function can remain preserved through neuromuscular adaptation; and clinical decisions should depend on the stability of that adaptation, not on aesthetic geometry alone.

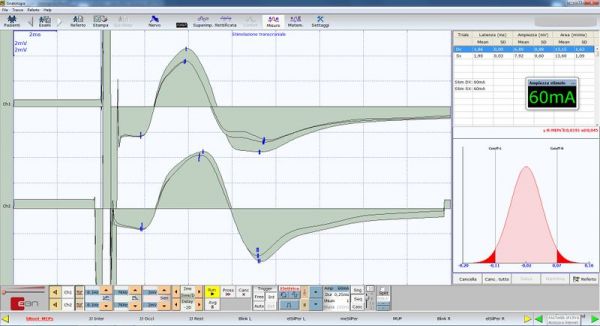

A paradigmatic clinical case illustrates this principle. A patient with a unilateral posterior crossbite and anterior open bite would typically be considered for orthodontic and surgical correction. However, the patient reports normal function and refuses therapy. Electrophysiological testing becomes the discriminating tool: bilateral transcranial stimulation and trigeminal reflex measures show functional symmetry despite visual asymmetry. The message is not that morphology is irrelevant, but that morphology must be interpreted through the lens of neurophysiology: the trigeminal system can preserve balance even when anatomy is imperfect.

Recent neurophysiological evidence reinforces this view. Experimental work shows that even minimal occlusal modifications can induce measurable cortical reorganization in face-M1 and face-S1, supporting the idea that the “face sensorimotor cortex” participates in the control not only of voluntary jaw movements but also of semi-automatic behaviors such as mastication and swallowing. Neuroplasticity can be adaptive—supporting functional compensation—or maladaptive—contributing to pain, instability, or decompensation when the system fails to recalibrate. Therefore, the central clinical question becomes: is the patient’s neuroadaptive balance stable, fragile, or already decompensating? Answering this requires integrating morphology, function, and measurable neurophysiological response.

Finally, the chapter concludes with a systems claim: the masticatory system is a complex system. Teeth, temporomandibular joint, periodontal receptors, muscle spindles, and trigeminal networks do not act in isolation; they interact and generate emergent behavior (for example, reflex patterns such as the masseter silent period). This view does not replace classical orthodontic and prosthetic knowledge—it enriches it. It proposes a functional, neurophysiological perspective capable of guiding personalized rehabilitation strategies with a higher respect for biological variability and adaptive limits.

In summary, Masticationpedia proposes a paradigm extension: from “occlusion” as static morphology to mastication as a neurofunctional, adaptive, and measurable system. In this framework, malocclusion becomes an insufficient heuristic category, and occlusal dysmorphism becomes a more precise clinical concept. Diagnosis and therapy must therefore be guided not only by shape, but by the dynamic neurophysiological balance that truly determines stability, resilience, and well-being.

Why this chapter matters

This chapter introduces the core intuition that will guide the whole Book:

- form is not equivalent to function

- symmetry can be preserved by neuromuscular adaptation

- “malocclusion” is often a morphological label without functional proof

- occlusal dysmorphism is a clinically safer concept

- diagnosis must integrate morphology, function, and neurophysiology

- treatment should respect (and measure) neuroadaptive balance, not only “shape”

- trigeminal neuroplasticity is the key to understanding stability vs decompensation

A paradigmatic example

Below: symmetry of masseter response under bilateral transcranial stimulation — a strong signal that the system can preserve balance even when morphology is clearly imperfect.

Keywords

Neuro-gnathology · trigeminal system · sensorimotor integration · neuroplasticity · complexity science · clinical epistemology · interdisciplinary diagnostics · occlusal dysmorphism · paradigm shift · orofacial pain

Access

Full chapter access is available to registered members via Linkedin while if you already have an account, please use “Member entry”.

You register as an Approved Expert using your LinkedIn profile. The team will send you the password to enter Member Entry.

Access the Reserved Area using the username and password sent to you. This function is reserved for members approved via LinkedIn.